How Frederick Douglass Found Power in Photography

Man is the only picture-making animal in the world. He alone of all the inhabitants of earth has the capacity and passion for pictures. — Frederick Douglass

If Frederick Douglass were alive today, what would he choose for his profile picture?

It’s not a trivial question. Though he lived more than 100 years ago, Douglass knew as well as any celebrity today that the way we present ourselves in photographs sends a powerful statement.

Photography was a brand-new technology in the mid-1800s, when Douglass came of age. Born in 1818 in Maryland as a slave, Douglass taught himself to read and write. At the age of 20, he escaped to the North and became a free man in 1846. About the same time in France, Louis Daguerre was developing an early form of image capturing and printing called the daguerreotype. His technology quickly spread to the United States and the world.

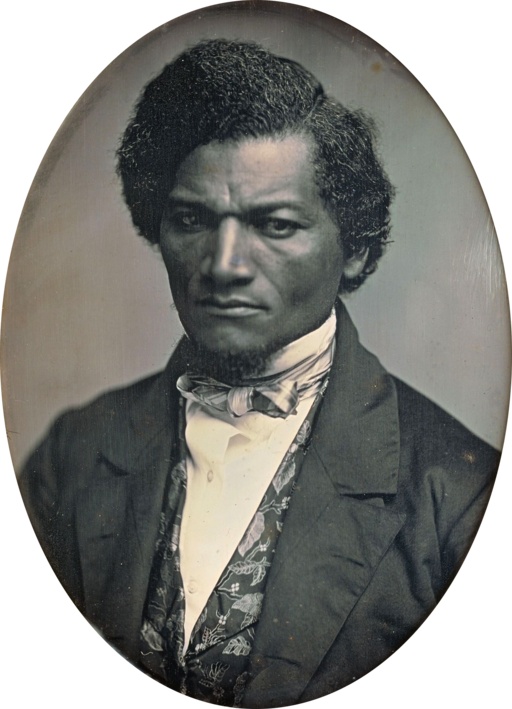

Douglass became fascinated with photography, sitting for nearly 160 photo portraits during his lifetime. In each of his three autobiographies documenting his life as a former slave and outspoken advocate for abolitionism and equal rights, he included his portrait, prominently displayed in the frontispiece. “The picture must be in the book,” he wrote, “or the book be considered incomplete” (qtd. in Meehan, 2008, p. 160).

Like social media influencers today, Douglass understood that carefully chosen, photographs could shape a public narrative. Slavery was still a fact of life when Douglass became a free man, and many white people held the belief that black people were physically and mentally inferior. By the late 1800s — post-Darwin — ethnologists were studying indigenous peoples around the world (they referred to them as “savages”) and comparing anatomical traits as evidence of racial superiority or inferiority (Haller, 1971, p. 714). The photos white photographers made often had the effect of dehumanizing non-Europeans.

Mindful of this, Douglass deliberately chose the image he presented to the public. Every photographic portrait made shows him dressed fashionably in a suit and tie with his thick hair (and sometimes, beard) neatly combed. His expression is serious and his eyes steady and piercing. His strategy in posing was to reclaim the power of what he called “photographic self-representation” (Douglass, 1861).

He saw the technology of photography as a potent weapon for destroying stereotypes and promoting equal rights for African Americans. In a 1861 lecture he titled Pictures and Progress, Douglass wrote, “Men of all conditions and classes, can now see themselves as others seem them — and as they will be seen — by those shall come after them.”

Provided, however, that the photographers were not manipulating the scene. Douglass believed the photographer inevitably held the power to represent individuals or groups of people as he wanted to see them. He observed that white photographers often used costumes and props to accentuate perceived physical and cultural characteristics that differed from the typical Europeans. Douglass wrote that the photographer “will invariably present the highest type of the European, and the lowest type of Negro” (qtd. in Meehan, p. 150).

Yet, Douglass remained optimistic that photography could not only show truth but also promote cross-cultural understanding and ultimately, equal rights. A review of Picturing Frederick Douglass, an anthology of photographic portraits of Douglass, states:

To Douglass, photography was the great “democratic art” that would finally assert black humanity in place of the slave “thing” and at the same time counter the blackface minstrelsy caricatures that had come to define the public perception of what it meant to be black. (Liverlight)

Though a rather new technology, photography in the late 1800s quickly became widely available and cheap. Every small town had a photographic studio and itinerant photographers would often travel in rural areas to offer portraits. Douglass commented, “The farmer boy can get a picture for himself and a shoe for his horse at the same time, and for the same price” (p. 9).

Unlike today, where we can take dozens of selfies and choose the one that flatters us the most in those days, the process of photography was slow and cumbersome. People prepared themselves to look their best. Douglass remarked, “Yet whoever stood before a glass [mirror] preparing to sit or stand for a picture — without consciousness of some such vanity?” And, he added, there would always be someone who would appreciate it: “A man’s picture, however homely, will, like himself, find somebody to admire it” (p. 9).

Douglass encouraged people to take control over their public image through photos. He called photography a “vast power” of “symbolical representation” that could create an air of mystery with an admiration bordering on religious worship. At the same time, photography could be used to reveal “truth or error” (p. 11).

“Men of all conditions and classes,” he wrote, “can now see themselves as others see them — and as they will be seen — by those shall come after them” (p. 7).

African American Photographers of the 19th Century

Augustus Washington (1820–1875). Daguerreotypist. Attended Dartmouth College. Emigrated to Liberia in 1852.

James Presley Ball (1825–1904). Official photographer of the 25th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. Famous subjects: Henry Highland Garnet, Queen Victoria, Charles Dickens, P.T. Barnum.

James C. Farley (1854-c.1910). First nationally known African American photographer. Gallery owner.

C.M. Batty (1873–1927). Led photography department at Tuskegee Institute. Famous subjects: Frederick Douglass, Paul Laurence Dunbar, W.E.B. Dubois.

References

Haller, J.S. (1971). Race and the concept of progress in nineteenth century American ethnology. American Anthropologist. 73, 710–714.

Liverlight Books. (2015). Review of Picturing Frederick Douglass by John Stauffer, Zoe Todd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier. https://web.archive.org/web/20160806065824/http://books.wwnorton.com/books/picturing-frederick-douglass/

Meehan, S. R. (2008). Mediating American autobiography: Photography in Emerson, Thoreau, Douglass, and Whitman. University of Missouri.